Is Your Nonprofit Ready for a Capital Project?

Is your nonprofit considering raising funds and investing in building or renovating a piece of property? Save time, money, and headaches.

10 questions to ask before your nonprofit commits to a big property project.

I have an almost-two-year old who just discovered Mega Blocks and how to stack them as tall as possible before they fall. That usually leads to some two-way negotiation about where the next block should go, to avoid a cascade of blocks and tears. (Sometimes the game is to build it high and knock it down, but that’s a Blue Avocado article for another day!)

Here’s where I tell you that nonprofit construction projects are something like negotiating with a toddler still practicing his stacking.

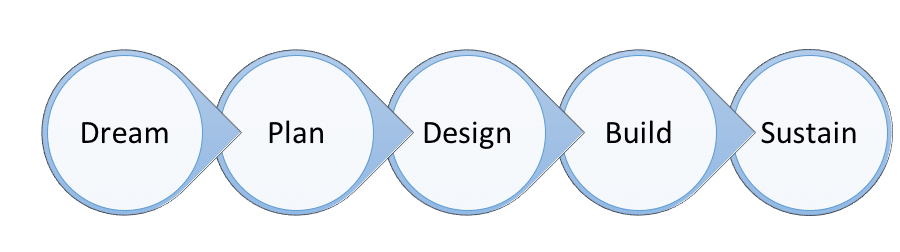

Fortunately, a real expert is here to move us from an awkward metaphor to some practical tips because a capital project — maybe you’ve outgrown your space or had a piece of land gifted to you from a donor — can be an incredible opportunity. But only if you are prepared. Kate Stephenson is a partner at HELM Construction Solutions in Montpelier, Vermont, and former nonprofit executive director herself. Here are her field-tested tips for your next capital undertaking:

Is your organization considering raising funds and investing in building or renovating a piece of property? If so, now is time to make sure everyone is on the same page about the goals of this major undertaking. Focused planning will save time, money, and (a lot of) headaches down the road.

Before taking the plunge, I suggest that you ask yourselves these ten key questions:

1. What’s your goal?

The first question when considering any capital project should be: How does this fit into your long-term strategic plan? You should be talking about where you see this organization in 5 to 10 years, and how the capital investment will advance your goals. Does the move advance your mission — or is there a risk it would detract from it?

2. What do you need?

Architects call this “defining the program.” But before you even bring an architect to the table, get very clear among your board, staff and supporters about the scope of the project. Here are some questions you can start the conversation with: Are we talking about cosmetic improvements to an existing space, an addition or a completely new building? Going back to the strategic plan, how many staff do we need to accommodate? What new programs do we anticipate? What services do we currently offer and how do we want to enhance them?

3. Is the organization financially healthy?

A strong financial track record and well-organized financial statements make all the difference in generating support from individual donors and foundations. Strong credit and assets will matter when you try to secure financing from a lender, too.

So ask yourself whether the board and staff have a strong grasp of the organization’s current financial situation and how this facilities project will affect it. If the organization’s future is up in the air in any way, then it is worth questioning whether it is prudent to invest in owning a facility, if renting or leasing might give more flexibility in an uncertain future.

4. Are we all on the same page?

Do you have a strong leader (or leaders) who will advocate for this project and push things to keep moving forward? You don’t want to stall out after you’ve started, and yet many organizations get stuck at this stage in the process. Some stakeholders are ready for growth and are excited to take on this new project and all of the potential that comes with it. Others are more risk-averse and don’t want to spend any money without a rock-solid plan in place. Sound familiar? Defining and articulating the scope of the project will help ensure everyone understands what they’re signing on for. Pro tip: A business plan or pro forma can be a great exercise in this step.

5. Who gets to be the decider?

Many nonprofits suffer from an enthusiastic group of volunteers who have lots of ideas, but there’s no clear process for how their input will be incorporated into the process. Do your executive director a favor and clearly delineate her or his authority relative to capital projects. Ask the ED to identify who should be consulted, then create a plan for how to solicit and summarize their feedback. Do this in the project planning phase, before design has even started. Then ask: what is the role of the board? Do they need to approve investments over a certain dollar amount? Do they need to review plans throughout the design process? Is there a board subcommittee focused on facilities planning and design?

6. What’s our timeline?

Whether you need to move within 6 months or 5 years will definitely drive your decision on whether to remodel or build from scratch. Even on a relatively small project, don’t underestimate the amount of time needed for design, construction and the actual moving process. In my experience with capital projects, a full month of design and planning for every month of construction is a good rule of thumb.

7. Who will manage the project?

Identifying this project manager role as early as possible is key. I can’t say that often enough. Most nonprofits I work with are already understaffed and juggling a million things — and that’s before taking on a major facilities project. There may be volunteers ready to serve on the building committee, but who will serve as project manager and ensure the project stays on time and on budget?

The best project managers usually come from outside the organization, someone who has a background in construction, permitting and planning. Part of the overall budget for the project should pay for this pre-construction oversight — whether it’s allocating a certain number of hours in addition to the regular duties of an existing staff member, or hiring someone from the outside as support.

8. Can we raise the money? Should we investigate a tax exempt bond or a bank loan?

Many nonprofits fall into the trap of the chicken-and-egg problem. They have a grand vision but no idea what it would cost to build, or how much money they can potentially raise through grants, donations and loans. If that sounds like you, the best solution is a parallel track process.

Start a feasibility study with a capital campaign consultant to help you define a realistic goal and timeline based on your current operating budget, annual fundraising track record and an analysis of your donor pool. As well, depending on the size of the project, you will want to consider whether a loan from a CDFI, a credit union, a bank or even issuing a tax-exempt bond are possible sources of financing. Whatever the type of financing you ultimately use, it will be necessary in the early schematic design phase to get a ballpark number for what it will cost to permit, design, construct and furnish the new facility.

If these two numbers are in the same range — great! If not, it’s time to start developing Plan B (and C and D, to be honest). Take into account any additional operating costs, such as staffing, financing, or maintenance, that the organization will have once the facility is completed. Often a capital campaign will include an endowment component to help cover these future expenses.

9. Are there any legal impediments to this project?

Unfortunately, too many organizations get a long way down the project planning road before determining whether their project is even possible at a given location. What permits are required before construction can start? What does the timeline look like for applying for and receiving them? Are there constraints related to zoning, historic preservation or occupancy at this site? Permit review is critical to pre-construction planning, and it shouldn’t be skipped.

10. What are the milestones when you will decide whether or not to move ahead with the project?

Planning any project of this scale is a constant information-gathering process. Most likely your building committee will be meeting regularly for many months before any construction starts in order to make sure everything is lined up, and that decisions are made. As part of your project schedule, define the key decision-making points that will determine whether the project moves ahead as planned. (These could be part of regularly scheduled board meetings or special sessions.)

Here are four typical milestones:

- At land acquisition

- Upon completion of schematic design

- Upon completion of preliminary estimates

- At permit submittal

As your board approaches these questions, have conversations about how much money you are willing to spend to get to the next decision-making point. You may have $50,000 or more in permitting, planning, design and capital campaign expenses before you can even decide whether to go ahead with the project.

It takes dedication, a lot of time and considerable financial resources to pull off a major facilities expansion or renovation. Get started on the right foot by putting the time in up front. With a solid plan in place, you’ll be able to raise money more effectively and achieve your strategic organizational goals!

Additional resources:

Nonprofit Finance Fund: Facility Planning Guides

You might also like:

- Do Nonprofits Pay Taxes? Do Nonprofit Employees Pay Taxes?

- Grant Writing Isn’t Overhead — It’s Infrastructure

- Re-Imagining Fundraising: How Funder Education and Systemic-Change Approaches are Changing the Game

- Your IRS Form 990 Questions Answered

- The Million-Dollar Question: What Could Your Nonprofit Do if Money Weren’t an Issue?

You made it to the end! Please share this article!

Let’s help other nonprofit leaders succeed! Consider sharing this article with your friends and colleagues via email or social media.

About the Author

Kate Stephenson is a partner in HELM Construction Solutions and acts as owner’s representative for a variety of for-profit businesses and nonprofit organizations planning facilities projects. She is the former Executive Director of the Yestermorrow Design/Build School.

Articles on Blue Avocado do not provide legal representation or legal advice and should not be used as a substitute for advice or legal counsel. Blue Avocado provides space for the nonprofit sector to express new ideas. The opinions and views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect or imply the opinions or views of Blue Avocado, its publisher, or affiliated organizations. Blue Avocado, its publisher, and affiliated organizations are not liable for website visitors’ use of the content on Blue Avocado nor for visitors’ decisions about using the Blue Avocado website.

I cannot express deeply enough my agreement with point 7 – budget for and employ a project manager. We entered a capital campaign over 7 years ago to build a senior center. We did do a feasibility study, their result was a very conditioned go ahead. We then entered a capital campaign in the middle of a recession. That did not stop us – we now have a senior center.

However as ED; in addition to running my organization and leading the capital campaign – I became the default project manager. This additional duty very nearly put me over the edge. I was a physical and emotional wreck by the time the building was finished. In addition, I hate to admit it, but some of the problems we are having with construction issues may not have happened if there was a professional project manager in charge. As much as I hate to admit (or believe), it seems apparent that the contractor took advantage of my inexperience. Working in the non-profit arena, with other professionals who live to improve the world, I found myself wanting to believe that others were dealing fairly with me, even when that was not the case.

Plus, project management is extremely time consuming. In spite of what I said above, I did not give the contractors Carte Blanche. I was extremely involved in construction meetings, plan review, site visits and inspections etc. It was literally a 20-30 hour a week job on top of my other duties.

So, as a veteran of a 7 year capital campaign, and a build; I heartily recommend that no one tries it without a separate, professional project manager.

Thank you for sharing your experience and thoughts on this topic.

Excellent article! I manage the C. Keith Birkenfeld Trust, a field of interest fund at Seattle Foundation which uses its resources primarily to fund capital projects with regional significance in rural counties around the beautiful Puget Sound. Following 11 years of funding, I’ve learned to add one more dimension to this excellent list. It has to do with the future: once built, can you afford to operate this terrific new building? For most of my grantees, they have exceptional ideas and aspirations; and, after a lot of hard and creative work, they can raise the money needed for land acquisition and construction. But for some it becomes an ongoing struggle to support the added expenses which come from a larger building and maybe more staff and programming. All of which is desirable except the part about stressing out over operating revenue. So, we’ve added questions about supporting program growth and added operating expense, and now request operating proformas to help us understand how the organization envisions paying for all of this. It’s very revealing to me and to the organization requesting funding. In many cases, the organizations revise their plans or begin cultivating new sources of operating revenue BEFORE the building is constructed. We’re all a lot less stressed out now and back kayaking again!

Thank you for sharing your experience and thoughts on this topic.